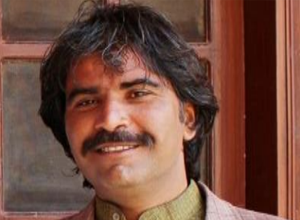

Kawish Latif Jokhio, a 28-year-old social activist from the underdeveloped and remote Badin district in Sindh province, has dedicated his energies to ameliorating the condition of scheduled caste Hindus, who face discrimination at the hands of both upper caste Hindus and Muslims. To help the members of this marginalized community – living in Badin district – realize their full potential, Jokhio built their capacity and motivated them to fully participate in the 2015 local government elections.

More than 2.5 million scheduled caste Hindus continue to be extremely vulnerable to discrimination, marginalization, and social exclusion in Pakistan. Suffering from acute poverty and rampant illiteracy, coupled with widespread discrimination against them, they do not wield political influence at any level.

At present, there are no seats exclusively reserved for the scheduled caste Hindus in the Senate, National Assembly, provincial assemblies, or local governments, implying that more often than not upper caste Hindus get elected on the reserved seats. Furthermore, the scheduled caste Hindus face significant socio-economic and political hurdles in freely exercising their right to enfranchise or in contesting elections.

The situation of scheduled caste Hindus in Badin district, regardless of their sizeable population, is no different from other areas where the community is more sparsely populated. With this in view, Laar Environmental Awareness Forum (LEAF), a local NGO funded by USAID Citizens’ Voice Project under Grants Cycle 6 thematic area ‘Importance of Local Government Elections’, focused on the empowerment of the scheduled caste Hindus in rural areas of the district.

LEAF organized capacity building sessions, training events, citizens’ assemblies, conferences, and forums to help the scheduled caste Hindus and other marginalized groups enter the political mainstream by creating awareness about their rights and informing them of their vote’s importance.

Volunteers like Kawish Latif Jokhio, who has a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Sindh, Jamshoro, were at the forefront of these interventions. “The local government system offers the solution to the problems of the underprivileged citizens; thus, they should be actively involved in it,” he said.

Jokhio’s efforts to inform and mobilize the community inspired Veerji Kohli, a young scheduled caste Hindu peasant, to not only become politically active but also contest the local government elections. Kohli lost the election by a narrow margin of 30 votes and came second, but his efforts to motivate and mobilize the marginalized communities inspired confidence among them and laid the foundation for their increased political participation.

“Garnering the second highest number of votes is an achievement in itself for Kohli. More important, he was also supported by those educated Muslim voters who wanted to bring about a positive change in the society,” says Ramoon Kohli, the coordinator of LEAF’s USAID-supported project. As Jokhio sees it, by aspiring to represent his community in the well-entrenched socio-political hierarchy of Badin district, Kohli has managed to impart confidence to many others like him.

Jokhio’s example speaks volumes of how USAID’s support has contributed to developing the social capital and inclusivity in Pakistan by enabling the members of marginalized groups to exercise their constitutional right to vote and, if some among them may desire, represent their community and area.